- Home

- Chris England

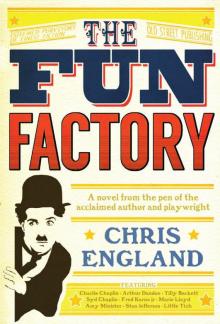

The Fun Factory

The Fun Factory Read online

Contents

Title Page

EXPLANATORY NOTE

PART I

1 COLLEGE LIFE

2 THE SMOKING CONCERT

3 OH! MR PORTER!

4 THE VARSITY B.C.

5 THE HOUSE THAT FRED BUILT

6 A NIGHT IN AN ENGLISH MUSIC HALL

7 THE MAYOR OF MUDCUMDYKE

8 FRED KARNO’S ARMY

9 WONTDETAINIA

10 HIS BIG BREAK

11 JAIL BIRDS

PART II

12 IT’S A MARVEL ’OW ’E DOOS IT BUT ’E DO

13 THE NEW WOMAN’S CLUB

14 MUMMING BIRDS

15 UNDER THE HONEYMOON TREE

16 THE KARNO OF THE NORTH

17 TILLY’S PUNCTURED ROMANCE

18 A VISIT FROM THE GUV’NOR

19 BESIDE THE SEASIDE

PART III

20 THE FOOTBALL MATCH

21 HE OF THE FUNNY WAYS

22 OUI! TRAY BONG!

23 LA VALSE RENVERSANTE

24 A WOMAN OF PARIS

25 THE TOSS OF A COIN

26 DON’T DO IT AGAIN, MATILDA

27 BREAK A LEG

PART IV

28 THE SOCIALIST

29 LET ME CALL YOU SWEETHEART

30 JIMMY THE FEARLESS

31 I’LL GET MY OWN BACK

32 THE GREAT DETECTIVE

33 TIED UP IN NOTTS

34 THE WOW WOWS

35 SHIP AHOY!

36 ALWAYS LEAVE THEM LAUGHING

NOTES

NOTES ON CHAPTER TITLES

HISTORICAL NOTE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Copyright

EXPLANATORY NOTE

THE memoirs that make up this volume came into my hands quite unexpectedly one day. When my wife and I moved into the house in Streatham where we have now lived for nearly fifteen years we became friendly with the elderly lady who lived in the ground-floor flat of the large house next door, a Mrs Lander. One day we happened to be talking about my interest in comedy and comedians, and she said: “Of course, my grandfather knew Charlie Chaplin.”

“Really?” I said, thinking to myself: yes, and Lloyd George too, no doubt.

“Oh yes,” Mrs Lander said. “They were really quite thick, apparently.”

It seems incredible to me now, looking back, but I didn’t really pursue the subject. Eventually Mrs Lander moved to a residential care home, and then a few months later her daughter dropped round to tell us that sadly she had passed away.

“She wanted me to thank you for your kindness,” the daughter said, “and asked me to make sure you had this.”

The battered old trunk she left me – which was brown, reinforced by wooden ribs, and secured by what looked like an army belt – had been used as a repository for the memorabilia of a career treading the boards. There were wooden swords and shields, in the Roman style, and a lion skin (somewhat past its best). There was some old-fashioned football kit, a red shirt with a lace-up collar, long white pantaloons, and big boots that laced above the ankle. There was also a big black cape, of the sort you might see a magician wearing, and a top hat.

Underneath all this, lying flat at the bottom of the trunk, were papers, including posters from old music hall and vaudeville bills, mostly featuring the sketches of the great Fred Karno. Tucked in amongst these charming relics were old black-and-white photographs of groups of young men and women posing together, sometimes in theatrical costume and make-up, sometimes formally dressed, often in front of steam locomotives.

Who were they, I wondered, and what had they been doing?

I inspected the old photographs more closely. Surely that dapper young fellow with the toothy smile was Charlie Chaplin? And who was that one, standing over to one side, captured in an instant glowering at young Chaplin as though he would cheerfully throttle him till his eyes popped out?

Well, the answers were to be found in a brown leather satchel right at the bottom of the trunk, in the memoirs of the owner, one Arthur Dandoe, comedian.

I have no reason to doubt that they represent a truthful account, and where Dandoe touches upon verifiable historical fact he is invariably accurate – considerably more so than his contemporary managed in his 1964 autobiography, at any rate. Indeed, this memoir covers a period very swiftly – one might almost say, dismissively – dealt with in that other volume, and seems to have been written in response to it, in the spirit of setting the record straight.

Readers can judge whether or not Dandoe is to be believed regarding more personal matters. In editing the papers, I have confined myself, more or less, to the addition of a few historical notes.

C.W. England

Streatham, May 2014

PART I

1

COLLEGE LIFE

“SO tell me – how did you get started?”

That’s what people always seem to want to know, as though finding out how mundane, how matter-of-fact, how accidental everything was at the kick-off will reassure them that it could all have happened to them, if only…

In point of fact the vast majority of theatrical performers I have met in my long and interesting life had the great advantage of being born into the game, never knowing anything else. Look no further than Chaplin’s autobiography. He paints a vivid, one might almost say melodramatic, picture of a childhood as the offspring of two music hall personalities. His father was a bona fide headliner, a baritone purveyor of faintly ribald singalong items who drank himself to death at the age of thirty-seven, and his mother was also a singer, who went by the name of Lily Harley. She lost her voice, and subsequently her marbles, and Charlie’s first exposure to the joys of being on stage came (he says) at five years of age. He had to stand in for her one night at the Canteen in Aldershot when she couldn’t face it, sang a song – “Jack Jones”, it was – scored a notable hit (of course, or it wouldn’t be in the book), and he was on his way.

I, on the other hand, unlike Charlie – and unlike Stan, whose father was a notable theatre impresario, and unlike Groucho and the boys, who were child performers with uncles and aunts in the vaudeville business – wasn’t born into it.

So how did I get started?

I take you back to Cambridge in the time of the old king, Edward VII, when the years, oddly (and evenly), began with “ought”. He was an enthusiastic visitor to the halls, by the way, old Bertie, used to come in disguise, but everyone recognised him, of course. His face was on the coins, after all.

So back in ought seven, it must have been, a glittering generation of carefree young things disported themselves about the old university town, sipping champagne in the sunshine on the banks of the Cam, flirting, carousing, occasionally dipping into a book or two, little dreaming that they were enjoying the last golden decade of the British Empire, and that the whole world order was just a few short years from changing for ever.

I was there too. Well, someone had to clean up after them, pick up their empties, make their beds, collect up their soiled laundry. And that someone was me. Arthur Dandoe, aged seventeen.

Not born into the theatre, you see. Born into servitude.

I’d lived in and around the college all my life. The school I went to until I was fourteen was just up the road. The little terraced house vouchsafed to the Dandoes by the college in its beneficence was about a hundred yards outside the main gate, up Trumpington Street.

All of my family belonged to the college, and had done going back into the mists of time. My mother, bless her, worked morning, noon and night in the kitchens, turning out exemplary breakfasts, luncheons and five-course suppers day after day. I wish I could say now that I miss my mother’s cooking, but the plain fact is I hardly ever got to taste any of it, certainly not

during term time. Her best work was destined for a higher class of palate than mine.

Lance, my brother, six years older than me, had returned to college dogsbody status after a stint in the army. He had served in Southern Africa during the conflict there, and despite many attempts by me and the other lads to get him to tell us tales of derring-do and glamorous hand-to-hand fighting with the filthy pig-faced Boer, I only ever heard him use three words to describe his active service. These three words were: “I shit meself.”

And there was my father. He was the head porter, which gave him a certain amount of status about the place. No one, whether he was a plummy-voiced undergraduate, a crusty old brainbox, a college servant or – it has to be said – a family member, ever addressed him as anything other than “Mr Dandoe”. Woe betide the unthinking fool who popped his head into the porter’s lodge and said something like, “I say, porter chappy…?” or, worse, “I say, Dandoe, be a good chap and hail me a cab, there’s a good fellow…”

The back would straighten, the nose would crinkle, the thumbs would work their way into the waistcoat pockets, and my father would say: “I’ve lived and worked in this college for nigh on thirty year, man and boy. I’ve risen, in that time, to the position of head porter, like my father before me, and as such I believe I have earned the right to be addressed as ‘Mister Dandoe’.”

He would lurk in his little room in the porter’s lodge, which was built into the side of the original fourteenth-century archway at the main gate, like some gigantic spider. The invisible strands of his web stretched out to the furthest extremes of the college, and he was sensitive to its minutest vibrations. Nothing got past him.

All his hopes of the Dandoe line continuing its tenure of the porter’s lodge were vested in me, and I was a sad disappointment to him on this score. He seemed to have more or less given up on Lance, partly I think because when his eldest left to join the army all those years ago he put his king and country before the college, and to my father’s way of thinking that was simply the wrong way round.

“One day, lad,” he was fond of saying to me, if possible within earshot of Lance, “all this will be yours. You’ll be master of all you survey.”

Every time he’d say this I would grind my teeth a little bit more.

My father got it into his head, as part of his grand plan for me, that I should familiarise myself with all aspects of college servitude, and in this spirit he allocated me a staircase, O staircase, to be precise, and I began a period as a probationary bedder. Now, college bedders – or bedmakers to give them their full title – were invariably women, usually matronly figures chosen precisely because of the sheer unlikeliness that they would inflame the passions of the young gentlemen of the college. As you can imagine, I was not overly thrilled to count myself amongst their number.

I got my own back by perfecting a wicked impersonation of my father with which I’d entertain the other college servants behind his back. I got his voice off so pat that I could actually put the wind up folk if I spotted them slacking. On one occasion I came across two of the bedders sitting on the stairs having a good old chinwag when they should have been working. I tiptoed up to a spot one flight below them and just out of sight, and realised, gloriously, that they were having a right old go at my father and his ways. Picking my moment – just when one of them had ill-advisedly described the old man as “a tartar of the first order” – I bellowed at the top of my (or rather, his) voice: “So! That’s what you think of me, Clarice Thompson!”

I then climbed the stairs and peeked round the corner to find that Clarice was in gibbering hysterics and her companion, most gratifyingly, had fainted clean away.

Lance claimed outright that I could never fool him, though, so imagine my joy when our father caught him one Sunday having a sly smoke in the Wren chapel.

“Lancelot Dandoe! What in the name of all that’s holy do you think you are playing at?” he cried, outraged, to which Lance, without turning round to look, retorted: “Fuck off, Arthur, you little bastard. I know it’s you.”

“Oh! I…! Oh!” my father spluttered, incoherent with anger.

“Fuck off, I said, or I’ll kick your bony arse for you, you scrawny little shite…”

Lance was twenty-three, and had been in the army, remember, but he was still carted unceremoniously out of the chapel by the lughole, looking like nothing so much as my father’s pet orangutang.

On this one particular morning, the morning of the day when it all started, I’d helped out with breakfast, I had whizzed around the rooms on O staircase with the duster, and I’d popped back to the kitchens, where Mum was able to slip me a piece of cold bacon and a couple of slices of bread. I had a bolthole near the library, behind a big ugly black-green statue of William Pitt the Younger, a celebrated college old boy, and I tucked myself away there to get outside my bacon sandwich and read a ‘penny blood’. You’ll remember these, I’m sure – little flimsy storybooks packed with lurid adventures of pirates and cowboys, kidnapping and murder. (I forget how much they used to cost, now…)

My favourite tales were the ones set in America. Partly it was the grandeur of the place, the huge snow-capped mountain ranges, the mighty plunging canyons, the vast, sweeping desert plains. If you’d been born and brought up in Cambridge then you could get a kick out of almost any geographical feature grander than a slight incline. Mostly, though, it was the freedom it seemed to represent, the freedom to go where you wanted, be what you wanted, to rustle cattle or prospect for gold, to stake your claim for a piece of the New World.

So there I was, hidden behind a likeness of one of our great Prime Ministers, when suddenly a horny hand grabbed my collar and yanked me out. I spluttered, showering crumbs and half-chewed bacon over my father’s coat.

“There you are!” he cried. “I might have known you’d be skiving off somewhere. What about your staircase? What about your beds?”

“Fimmished…” I coughed. How did the old spider know I was there?

“Well, then why aren’t you laying out the luncheon in the Great Hall?”

“I was juft…”

“How on earth do you expect to ever get the lodge with this sort of attitude? Do you think your grandfather rose to become head porter of the college by lazing about the place? Do you think I gained that position in my turn by slacking off and backsliding?”

“Don’ wamp it…” I mumbled, still struggling with a mouthful of crusty bread. I don’t know where the nerve came from to answer back on this particular day. Ordinarily I’d have let the storm blow itself out.

“I beg your pardon!”

“Don’ wamp lodge. Don’ wamp be head porper…!”

My father had hold of the lapels of my jacket, and in his frustration he began to shake me, which didn’t help me to get rid of the mouthful of sandwich.

“Well … what do you want, then, tell me that? Tell me what glorious plan you have devised for yourself?”

I took a breath, a couple of furious chews, and swallowed. Then I looked up at my father, his exasperated face shining red.

“I … want to go to … America,” I said.

“America!” he scoffed, investing that one single word with every morsel of scorn he could muster. “I suppose we’ve got this trash to thank for that bright idea, have we?” He snatched the story from my hand and flicked through it contemptuously. “Well, young man, you can do the late rounds for me all this week. That’ll give you some time to think about the error of your ways.”

There was a curfew in operation at all the colleges and any student spotted on the streets after eleven at night by the ‘bulldogs’,1 could be fined the finicky but traditional sum of six shillings and eightpence – a third of a pound – and repeated infractions could result in a student being sent down, which meant sent home. Cambridge, you see, thought so much of itself that the only way was down once you left the place, even though geographically speaking it was so near to sea level that almost everywhere else was up.

The college, too, could levy a fine, called ‘gate pence’, to be paid to the porter, whose job it was to apprehend any bright spark trying to avoid stumping up this pittance by clambering in the back way. The well-oiled undergraduate would regard this as a kind of local sport and would think nothing of dumping you on your backside in an ornamental lily pond before shouting “Hullooo!!” and disappearing over the horizon. My father, understandably, had tired of this treatment over the years, and, as soon as I was big enough to take care of myself, doing the late rounds became his preferred punishment for me. Actually, I didn’t mind too much, as I soon realised that if I managed to catch anyone and get gate pence off them I could trouser it myself.

Later that evening, then, after the nobs had had their five-course dinners and their brandies and their ports, and everyone else had toddled off to bed, I was dawdling behind some bushes in New Court with a clear view of the single-storey bath house. I’d heard some rustling in the street outside as I passed the back gates, you see, and I suspected that someone was about to make an attempt.

Sure enough, after a moment or two I heard the telltale straining of some hero launching an assault on the north face of a lamp post, and then a leg was slung over the wall, followed by a backside, and finally a complete human form lay silhouetted against the lamplight playing on the building opposite.

To my astonishment, it was a woman. She was wearing a green frock, padded out by a number of petticoats, by the look of things, and she paused for a moment, panting in a most unladylike fashion from the exertion of the climb, before beginning to slide a shapely leg gingerly down the roof towards me.

I was delighted, because if some young rogue was trying to sneak a lady into his rooms then he was committing a serious sending-down offence and I should be able to extract a little more than just gate pence from him to keep his secret.

I watched for Romeo to make his appearance, but strangely there was no sign of him. Juliet, meanwhile, was leaning rather precariously over the guttering, and suddenly lost her grip, toppling headfirst into one of the large bins full of kitchen refuse. Well, I’m not sure what was in there that particular night, but nothing you’d want to be upside down in, that’s for sure. I broke cover and went to lend a hand. The lady had toppled the big bin over on its side by the time I reached her, and was truffling around in there looking for something. With an “Aha!” of triumph, she emerged, clutching her prize – covered in bits of potato peel and suchlike but still recognisably a rather fancy wig with lots of ringlets.

The Fun Factory

The Fun Factory