- Home

- Chris England

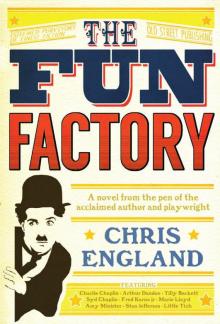

The Fun Factory Page 24

The Fun Factory Read online

Page 24

The music reached the end of a phrase, and as it began a new sequence Chevalier suddenly reached forward, snaked a long arm around la belle Mistinguett’s waist, and swung her bodily around. She shrieked with surprise as both feet left the floor, and then held on for dear life as Chevalier galloped frantic circles around the room on his great long legs, one-two-three, one-two-three. He’d clearly decided to seize the moment, and give Mistinguett a dance she would never forget.

People at other tables jumped to their feet to watch, clapping their hands and laughing, and Mistinguett’s big skirts swept their chairs aside, sending bottles and glasses flying.

A waiter came scurrying over to start clearing up, and just as he bent to start sweeping up some broken glass into a dustpan around came the whirling, swirling couple again and sent him sprawling. The crowd hooted with glee and pressed themselves against the walls to keep clear of the mayhem. Chevalier and Mistinguett, locked together now, bounced giddily off the bar, and a champagne bottle was dislodged by the impact and sent rolling towards the edge.

Round and round they spun, without tiring, and you began to feel like they would never bring the dance to an end. Certainly Chevalier showed no inclination to release Mistinguett now he had her in his arms, and she was not complaining either.

I found myself standing next to Monsieur Banel, the manager, who had tears of laughter streaming down his face.

“Hey, Monsieur,” I said. “How do you like this new sketch of Chevalier’s? Not bad, eh?”

I saw surprise, then calculation, then delight flit across his features, before he waved the orchestra to finish, and embraced the couple, who had come to a standstill in the middle of the room.

“Magnifique!” Banel cried, mopping at his face with a big white kerchief, as my friend the interpreter whispered: “Magnificent!”

“Mistinguett et Chevalier ensemble! Ça sera une sensation!” Banel beamed, and you could almost see his mouth watering at the prospect of putting this spectacle on his stage.

The two dancers were still holding onto each other and gazing into each other’s eyes, panting, oblivious. Banel turned and led the tumultuous applause which suddenly broke out, before urgently ushering his staff to begin to clear up the debris. King Alfonso XIII of Spain, meanwhile, was tight-lipped, bitterly regretting not seizing the moment.

The two lovebirds began work on their new sketch the very next day, and by the beginning of the week following it was ready to make its debut at the Folies. I didn’t see much of Maurice during that time, although whenever I did he was effusive in his gratitude for my having suggested to Banel that the wildly energetic dance would make a fine comic routine. The sketch, entitled La Valse Renversante, was an immediate triumph, a succès d’estime. They worked it up so that the two main characters, absorbed only in the dance and their besotted devotion to one another, danced obliviously around a set which was like the foyer of a grand hotel. They smashed and overturned furniture, discombobulated the hotel’s staff and guests as they passed to and fro, with great timing and finesse actually, and finished up with a brilliant coup whereby they rolled themselves entirely up in the carpet, still dancing, leaving just their heads sticking out of the top of the roll for the last chords of the music.

It was a sure thing, you could tell the first time you saw it, and the thing that really sold it above all was that you could see right off that Maurice and Mistinguett had fallen for each other and weren’t just putting it on for the act, and a Parisian crowd loves a real-life romance almost as much as it loves looking at semi-naked ladies. As their first week wore on it seemed to take them longer and longer to unroll themselves from the carpet for their bow, as they were unwilling to disengage from the embrace, until one night the curtain went down with them still wrapped up together, the audience cheering and hooting. Afterwards I asked Maurice what had happened.

“We could not unravel because … of my embarrassment. To be so close to that ravishing creature, you understand…?”

“Surely you could have hidden … your embarrassment.…” I said. “With a bow? Or perhaps your hat?”

“Yes, perhaps,” he agreed solemnly. “If only I could persuade her to let go of it.”

Back to the first night they performed it, and of course they were thrilled. Banel was delighted that his faith in Chevalier had been vindicated, and there was much back-slapping and cheek-embracing all round.

Max Linder, beaming with pleasure for his friend, kissed Maurice on both cheeks.

“Pas seulement la voix, eh? Mais aussi le corps magnifique!” he cried.

“Celebration!” Mistinguett declared above the hubbub, and the whole party decamped to a fancy restaurant a few streets away, which in my memory is illuminated in gold by three massive chandeliers. There was some sneaking out by the stage door, too, because Mistinguett wished to avoid the attentions of King Alfonso XIII, and Maurice had not been home to mad Marguerite for a week and a half.

The huge room was packed with the fashionable beau monde, with barely a spare seat anywhere, but somehow the appearance of Mistinguett galvanised about twenty waiters into action, and we were all shortly seated at a massive table created from numerous others that had been pushed together and covered in new white tablecloths.

Before long the champagne and bonhomie were flowing in broadly equal measure, and we were getting on the outside of some huge platters of shellfish, which were served on what seemed to be upturned bin lids.

Suddenly Maurice hissed: “Look! It’s Charlie!”

And indeed there, on the far side of the room, was young Mr Chaplin, enjoying a tête-à-tête with a young lady. Maurice hailed him at top volume.

“Hey! Charlie! Ho!”

Charlie looked pretty shocked to see us. He said something to his dinner companion, who was sitting with her back to us. She had long black hair, curled into ringlets, so I gathered, even in my champagne-and-cognac-fuddled state, that this was probably one of Mistinguett’s chorus girls.

“Come!” Maurice shouted. “Join the party!”

Charlie put his hand up to say that no, he and his paramour were just fine over there, but it was Maurice’s night, and he was not taking no for an answer.

“Come on! Both of you! I insist!” he cried, as he got up and in a handful of gangling strides crossed the restaurant to Charlie’s table. I was leaning drunkenly over the back of my chair, giggling at Charlie’s discomfiture.

Mistinguett now, full of the joys of life, saw her new young lover had left her side and peered around for him.

“Tell them!” Maurice shouted to her, across the heads of a number of late diners, some of whom were irritated to be disturbed by this boorishness, while others seemed to be enjoying the little free cabaret, as I was. “Tell them they must join us! This is our night, the night for celebration!”

“Qui est-ce?” Mistinguett called.

“C’est Charlie,” Maurice called back, indicating with his open hands. “Et sa jolie demoiselle.”

“Mathilde? Mais elle doit être ici, avec nous! Mathilde! Mathilde! À moi, vite-vite…!”

Charlie’s companion could hardly refuse such an insistent invitation from her distinguished employer, and so she turned to face us.

The busy chatter of the restaurant seemed to retreat suddenly, leaving only the pounding of my own blood in my ears.

It was Tilly Beckett.

24

A WOMAN OF PARIS

I woke to screaming, not sure where I was or what was happening. I was still trying to unscramble my wits when a tiny figure burst into my room and stood, sobbing, on the mat in her bare feet.

“Monsieur Art’ur! Monsieur Art’ur!”

It was Amélie, the thirteen-year-old première danseuse from the Folies, who was staying with her mother and sister in our hotel.

“It is Monsieur Charles! He is…” Here she broke off, choked with emotion. “Dead!”

There is an undeniable frisson of excitement when you think you might have killed

someone with the power of your bare hands. A moment of raw masculinity, something like that. And France, as a nation, and as a legal system, recognised the crime of passion as a legitimate defence, so I might even have got away with it.

I had the grandmother and grandfather of all headaches, though whether this was from the drink or from being run into a wall like a bull I wasn’t sure. I lurched up into a half-sitting position, and grunted: “Dead?”

I just about managed to focus my eyes on little Amélie, who was looking at me, appalled, as though horror was piling upon horror. Her hands flew to her mouth, and then she filled her lungs and let out another almighty scream as she fled.

I got myself to the basin, which seemed to be full of pink water, like some sort of medicine. I splashed my face with the stuff and it got even pinker. Aha… That would be blood then. I then caught sight of myself in the shaving mirror and realised why Amélie had run for her life. I looked like an ogre, battered, swollen and bloody, with a fat lip, one eye half closed and a lump like a goose egg on my forehead.

I grunted, and shambled my aching carcass into the next room to check on Chaplin.

I could see – actually any fool could have seen – his chest rising and falling, but he’d taken such a battering that all the screaming and palaver hadn’t woken him up, and there was blood trickling from the corner of his mouth. I gave a little harrumph of satisfaction.

As I shuffled across the corridor I passed little Amélie cowering in the corridor.

“He’sh not dead, more’sh the piddy…” I snarled, then went back to bed.

Of course, we’d kicked off at the restaurant. Tilly stood up, and I met her halfway across the room.

“Tilly?” I said, still not wholly believing my eyes.

“Hullo, Arthur,” she said, keeping hers downcast. “I’d better … you know…” She hurried over to answer Mistinguett’s summons.

“Well?” I said, turning to confront Charlie. “What have you got to say for yourself?”

“I really haven’t done anything wrong, have I?” he bleated shiftily.

“Haven’t done anything wrong?” I shouted. “You know, you know, that I have been looking everywhere, trying everything I know for a year to try and find Tilly, and now here I find you blithely sitting here having a secret romantic dinner with her as though it was nothing!”

“Listen, I couldn’t tell you, could I? She asked me not to.”

Maurice was putting two and two together. “Mathilde? Mathilde is the girl? Oh là là…!” Apparently French people do actually say that when surprised.

“That’s right!” I bellowed, “and this little weasel has been sneaking around with her behind my back!”

I grabbed a fistful of his shirt front and pulled him up onto his feet to oblige him to face me like a man. I planted myself foursquare, feeling the need, I must admit, to keep my balance against the effects of the celebration, and gathered myself to deliver Retribution with a capital R.

The room gasped as I swung my fist at Chaplin, who ducked, lightning fast, and then scurried away on all fours between my feet and stood up behind me. The indignity of it! I lumbered round to confront him again, swung my fist at his head, and he did the same thing again, popping up behind me like a jack-in-the-box.

Now the whole restaurant seemed to be laughing and cheering, which only enraged me more. I was trying to kill him, and the little bastard was scoring laughs off me!

It was too much. I gave up on the haymakers and jabbed my fist forwards at his face, trying to slow him down. He swayed left, making me miss, and then swayed right, and I missed again. I drove another big punch at his chin and he disappeared between my feet once more. This time when he popped up behind me he kicked me up the backside.

Hoots of laughter were ringing round the restaurant now, and I changed tactics, my cheeks burning with embarrassment. I decided to give chase, and Charlie dodged away around one large round table and then another. We found ourselves suddenly facing each other across a smaller empty table. He feinted one way, and I matched him. He made to go the other way, and I blocked. He went one way and then the other, and I mirrored his moves, and then grasped the table and hurled it aside to grab him in a bear hug. He turned to flee, but wasn’t fast enough, and I managed to grab hold of him from behind, pinning his arms.

Before I could work out what to do next, though, Charlie ran up the white-shirted barrel chest of a fat gentleman sitting at the table opposite – yes, ran up him – and twisted out of my grasp, so that he was now horizontal, with his feet on the fellow’s shoulders either side of his pop-eyed gasping red head, and his hands on mine. On the way up his feet kicked over a large plate of mussels, which went flying down the cleavage of the fat gentleman’s wife, and everyone at their table screamed. Charlie and I were momentarily face to face. He planted a kiss on the end of my nose and sprang to freedom.

I roared incoherently with rage, but all of a sudden I couldn’t move. Strong hands had taken hold of my arms and legs, and I suddenly found myself being carried bodily out into the street by four burly waiters, with applause inexplicably ringing in my ears. As they shoved me roughly through the glass doors and dumped me onto the pavement, I saw to my satisfaction that Charlie was being similarly dumped some six feet away, and prepared myself to continue hostilities right away. However, Maurice had followed us out and barred my way, while Ernie had hold of Charlie, who otherwise, I think, might have just bolted into the night.

“Non, my friend!” Maurice urged. “You must not fight in the street, it will be a night in prison for both of you.”

I saw the sense in his argument, particularly as two gendarmes were at that very moment eyeing us suspiciously from across the boulevard.

“He’s right,” Ernie said, although Charlie needed little persuading to back down. He wasn’t expecting what Ernie said next, though. “We’ll settle this back at the hotel, come on. Queensberry Rules, like Englishmen.”

Ernie, of course, had been a prize fighter in his time. He was only a lightweight, but he was certainly imposing enough to bend Charlie to his will, and I was mustard keen. Maurice waved and blew a kiss through the picture window at Mistinguett, who was peering out into the night, and by her side I saw Tilly, also watching, her expression unreadable.

At the hotel we went straight up to Ernie’s room. He made us take off our shoes so as not to disturb people in other rooms, and Charlie and I stripped down to shirtsleeves and braces. Ernie stood between us, a hand on each of our chests, and said: “Right, let’s do this thing. No kicking, no gouging, and hands off the family jewels. You get me?”

We nodded, tensed, and Maurice began to snigger. We glared at him.

“I’m sorry,” he giggled. “It is all so … noble!”

Now that he couldn’t back out of it Charlie was as ready for battle as I was, and when Ernie stepped back he came at me, landing a couple of light blows to the sides of my head, which I swatted away derisively. I thumped him on the chest, which took some of the wind out of him, and then we went at it in earnest.

Charlie danced around on his toes to begin with, trying to stay out of my reach. There were none of the crowd-pleasing comedy antics he’d employed in the restaurant, apart from one occasion when I rushed him, trying to get to grips, and he sidestepped so that I ran headfirst into a wall. I gave him a ringing thump on the ear, which slowed him down a bit, then he tried to brain me with a chair, but Ernie pinned his arms by his sides and gave him a stern talking to, which I’m not sure he could hear, on account of the ringing.

Finally I caught Chaplin with a big flailing open-hand slap which rattled his jaw and echoed off the bare walls like a gunshot ricochet. He stepped back and put his hands up, then began to feel in his mouth for loosened teeth. There was blood on his fingers, and I think he had bitten his tongue. I waited, poised to finish him off.

“C’est fini!” Maurice cried, and led me to the far side of the room. I was too tired to protest. I looked up and saw that there was

blood on the wall and on the ceiling.

And the next thing I remember is that silly girl screaming and waking me up.

In his autobiography, by the way, if you care to take a look at his account of the month we spent in Paris, you will find that Charlie says he had this fight with Ernie Stone. I suppose this is so he doesn’t have to mention me, or the fact that he was entirely in the wrong and deserved everything he got. It also makes him sound like a tough little scrapper, doesn’t it, to have fought an ex-professional boxer to a standstill. We can’t both be right, can we?

I didn’t speak with Tilly for several days, even though I now knew where she was and how to find her. Partly I wanted to wait until I was at least presentable, having received absolute proof that my face was capable of scaring children, and partly I was cross with her for not making herself known to me.

I saw her, though, now I knew to look for her. In fact I could hardly believe I’d managed to miss her. It was the dark hair that had thrown me, as all my daydreaming (and night-dreaming, for that matter) of her had recalled her lovely fair locks. But there she was, not only one of Mistinguett’s chorus, wearing very little, this fact concealed artfully behind a pair of giant feather fans, but also as a shocked hotel maid trying to keep vases and glasses from crashing to the floor as La Valse Renversante whirled on its merry way. I took every opportunity to watch her in action, but couldn’t quite bring myself to approach her backstage.

I didn’t speak to Chaplin either, and he didn’t speak to me. I wasn’t interested in his self-justifying wheedling, and in any case his mouth was so sore that he couldn’t have spoken even if he’d tried to. The Drunken Swell appeared even more drunken than usual, while much of the change to the Magician’s appearance was fortuitously masked by his moustache.

On the last night of our month in Paris, with the prospect of the boat train for Calais first thing in the morning, I finally decided that it was time. After our last performance of Mumming Birds I dodged my share of the packing up and slipped around front of house to watch the second half of the bill, which contained Tilly’s appearances, and then I went backstage.

The Fun Factory

The Fun Factory