- Home

- Chris England

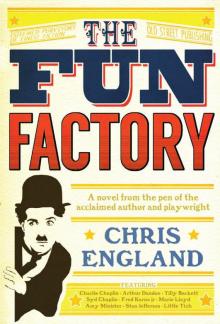

The Fun Factory Page 4

The Fun Factory Read online

Page 4

And who do you think was in line to be lizard lunch? That’s right, yours truly.

The conceit of the show, as you can probably guess from the title, was to depict Cambridge in prehistoric times. Rival groups of cavemen from rival caves would compete in a variety of activities which aped – rotted, I should say – college life, with the whole scheme enlivened by the appearance of the mechanical dinosaur.

Mr Luscombe and I had relatively small parts to play, as cavemen from ‘St Botolph’s cave’. I was Caveman 4, and I’m pretty sure that Luscombe was Caveman 3. There was a deal of standing around in animal skins, and numerous scenes in which twenty or more of us were running around trying to bop one another on the head with papier-mâché clubs. Caveman 4’s moment in the sun came near the end. It turned out, wouldn’t you know it, that I had been secretly working to further the interests of the Trinity cave, and I got my comeuppance when I was devoured by the brontosaurus.

One evening the company were just finishing a run-through in the club’s private rooms, which were above Catling’s sale rooms near the Corn Exchange, and I was busy dispensing whiskies-and-waters when Browes burst in, mopping his face.

“I say, you chaps, I’ve some frightful news!” he cried.

“Whatever is it?” the Rotter said, steering him to a chair, while I ghosted alongside, manservant-like, stiff drink at hand.

“A fellow on my staircase is writing a thesis…” – a collective shudder went through the company at the very thought of this – “about … well, about good old Brontie, actually!”

“No!” someone gasped.

“Yes, I assure you, so I told him – in strictest confidence, of course – about the climax to our show. I thought he, of all people, might be amused, but do you know what he said?”

“Go on,” the Rotter said, upper lip stiff as an ironing board.

“He said to me, he said: ‘Browes, you priceless ass! Don’t you know that the brontosaur was herbivorous?’”

After a moment Rottenburg smiled, and snorted, relieved: “My dear chap, so we got the name wrong. We’ll just call her ‘Herbie’ instead. Problem solved…”

“No, no, no! Herbivorous! It only ate plants! It couldn’t possibly eat a chap! The whole ending’s ruined!”

There was a grim silence. The Rotter shook his head slowly from side to side, much like Brontie herself. Did I mention, by the way, that Brontie was female? She had to be, do you see, because of a truly awful line in the closing number about her being one of the Brontie sisters.

“I’ll have to give this some thought,” The Rotter declared suddenly, then strode urgently out of the theatre. “Some serious thought!”

Next evening we all gathered again, desperately worried that the whole show had been fatally undermined. Cigarettes were smoked, carpets were paced. Everyone was convinced that the show was done for, but we reckoned without the never-say-die spirit of our president. He burst in with a big grin on his face, flourishing a drawing he himself had done.

“I’ve added a small scene, solves the whole thing. The chap, do you see, Dandoe here, has to spy on the other cavemen to find out what they are up to. Do you follow me? So he dresses himself up as a tree, ergo, dear Brontie can chomp him up with a clear conscience. Voilà!”

A resounding cheer went up at this elegant solution, and I doubt whether the man who discovered the actual brontosaurus ever had acclaim to match it.

And as fellows like the Rotter and Browes and Lord Peter Bradshaw thumped me genially on the back it really felt like we were all in this great enterprise together, as equals.

As the opening night approached, however, I began to wonder just how equal we all were. Because when the two technicians from the engineering department, Rottenburg’s assistants, Mr Ernest and Mr Kenyon, began supervising the installation of the monster, it became dazzlingly clear to me that the reason why I, of all people, had been selected to be Caveman 4 was that being eaten by the mechanical dinosaur was actually going to be pretty bloody dangerous.

The beast weighed a ton for a start. It consisted of a solid wooden framework, strong enough to hold three men inside, covered with canvas which was painted to look like the giant reptile’s skin. Then there were – I don’t know how many. Seven? Eight? – huge blocks with pulleys on, any one of which could have killed a man on its own if it came loose and fell on him, not to mention the further tons of scaffolding which Mr Ernest was reckoning on using to attach the whole contraption to the ceiling. As the man who’d be standing on the spot marked with an X, I quickly saw that if the slightest thing went wrong I was the one for the chop.

The only way they could make a victim – me – disappear whole into Brontie’s mouth was by positioning Mr Ernest inside the neck to haul me in bodily, with Mr Kenyon further up holding onto Ernest’s ankles. No fewer than eight others were concealed in the wings, yanking on ropes, pulling levers, throwing sandbags on and off, and they just couldn’t seem to get it right.

I was watching from the wings with my heart in my mouth the first time they tried to lower the head to the stage and smashed the chair they were using for target practice into matchwood.

On another occasion the neck started careering up and down uncontrollably. The stagehands were trying to grab hold of a counterweight which would have brought Brontie under control, but it kept bobbing out of their reach. Finally three of them caught the creature’s head as it smashed heavily into the stage for the umpteenth time, and Mr Ernest and Mr Kenyon slithered shakily out onto the floor.

“Most invigorating,” Mr Ernest said, an idiotic grin on his face.

Finally, well after midnight on the day before the opening performance, Brontie was deemed safe enough to attempt to eat me. I said my line (and a silent prayer), the monster’s head came down, my leaf-covered torso disappeared into its jaws, Mr Ernest grasped my arms, and we all swung up into the flies.

Despite the triumphant cheers and whistles from the rest of the company, I had a strong suspicion that my first appearance on the stage could easily turn out to be my last.

Come the opening night the New Theatre was packed to the rafters with students and local townsfolk, all drawn by the Rotter’s proclamation that this was to be the first time a great dinosaur had been portrayed on the live stage anywhere in the world.

Mr Luscombe and I peeked out through a small gap in the curtain at the crowd milling about, finding their seats.

“I say,” Luscombe hissed. “Did you hear?”

“Hear what, sir?” I whispered.

“Word is that some big noise from London has come up on the train specially to see Brontie in action.”

“What sort of big noise?”

“Oh, our director has contacts, you know, in the London theatre. Sssh! Here he comes…!”

The Rotter shoved his big, square rugger-pug face in between ours and surveyed the scene.

“Full house! Good luck, gentlemen, which is to say, confound it, bad luck. Break a leg, I mean. Break all your legs!”

He shovelled us ahead of him into the wings and gave Mr Ernest the signal to begin. The curtain rose, and we were off.

The show itself trundled along agreeably enough to begin with. The Rotter stomped around backstage as his small army of cavemen galloped on and off for the various scenes and musical numbers. Every now and then there would be an unexpectedly big laugh, and he would note down what had provoked it on his script with a scrawled tick. Then he would resume his nervous pacing, occasionally pausing to give a silent pat of encouragement to someone with a huge paw.

Although the audience were enjoying themselves, there was a palpable air of anticipation about the place. Everyone was waiting to see this much-vaunted brontosaurus. The Rotter himself was pacing nervously, sometimes reaching up to twang one of the control ropes above our heads.

Finally, towards the end of the evening, it was the moment. A flurry of hushed activity suddenly bustled around the contraption, and Mr Ernest and Mr Kenyon wriggled into its ne

ck. The ropes were pulled taut, and the eight stagehands took the strain. I hadn’t time to watch any more, because I had to be onstage.

Trinity cave were having a secret pow-wow, discussing their plans for the big contest on the morrow. Suddenly they noticed that a small shrub was inching towards them, as if to hear better. In a trice I was exposed, I stood up, and I delivered my line, my only line of the show: “I did what I did for the sake of the cave! The dear old cave!”

Brontie let out a terrifying roar (which is to say, a stagehand called Nicholas bellowed into a barrel). This was the cue for everyone else in the scene to scarper, except me. One or two ladies in the audience let out an excited shriek of anticipation.

And nothing happened.

I glanced over, and saw the Rotter frantically lashing one of the ropes backwards and forwards. It seemed to have snagged in its pulley high up in the ceiling. The Rotter waved desperately at me to fill, and booted young Nicholas up the backside. Brontie promptly let out another, slightly aggrieved, dinosaurific roar.

I remembered something I’d heard, and for want of anything better to say decided to impart it to the audience.

“Uh-oh! That sounds like it might be a brontosaurus, you know,” I said, putting on my best scared face. “Those of you who have been keeping up with your studies will know that the name brontosaurus means ‘Thunder lizard’. So named, I’m told, for its terrifying roar…”

Nick, obligingly, let loose with another blood-curdling bass bellow, and the audience looked expectantly over to the side of the stage. I could see what they couldn’t, though, that the Rotter was still trying to free the snagged rope.

“Although…” I said, and watched the eyes snap back to me. “Since its diet was in fact exclusively vegetarian, some of our finest scientists now believe the thunder may have emanated from the other end entirely.”

The laugh I provoked with this line washed over me like a breaker and I felt the tingle of the Power once again. I could see the white dress shirts and black dinner jackets stretching to the back of the stalls, and the browns and greys and blues of the folk in the upper circle.

I heard the Rotter give a stifled cry of triumph and realised that the rope must be free, but I wasn’t ready to be eaten just yet.

I stepped forwards off my mark and down towards the footlights.

“I spent the morning hunting, don’t you know?” I found myself saying. “Not terribly successful, I’m afraid. I was trying to bag a very tricky kind of dinosaur. The Ran-off-as-soon-as-he-saurus…!”

Huge laugh. I watched it, waited for it, bathed in it.

“What you don’t want, though,” I went on, when the moment was just right, “is to come across one of those fearsome predatory dinosaurs. Something like the He’s-got-it-in-for-us…”

Another good laugh. Suddenly Brontie uttered the most bone-chilling roar. I glanced to my left and saw that the Rotter, his face purple with rage, had grabbed Nicholas’s barrel and was howling all his frustration into it. I quickly reckoned maybe I had pushed my luck far enough, and skipped back to my spot, quaking with pretend terror.

“Ooooh!” went the audience now as Brontie’s massive head lowered itself slowly from the flies, and one or two clip-claps of applause broke out.

“Raaaargh!” went the Rotter.

The jaws slid neatly over my head and shoulders and I reached up to grab Mr Ernest’s clammy hands.

“Ran-off-as-soon-as-he-saurus, that’s a good one…” he was chuckling to himself. The great contraption swung into the air. I could hear the muffled sound of the audience’s applause, suitably impressed. Then suddenly…

Twang!

Something snapped, something gave, and the head, having moments before disappeared triumphantly into the sky, now hurtled down and smashed into the floor. The audience, startled and unsure as to whether this latest development was intentional, half-laughed, half-screamed. I was thrown out – regurgitated, as it were – and rolled halfway across the stage. Without my weight in it, the dinosaur’s head lurched up again and banged into the metal walkway, which was masked from the audience’s view by the tab. In the wings the Rotter was furiously waving me to my feet, clearly intent that Brontie should eat me once again.

I turned to the audience.

“I told you she was a vegetarian,” I said.

Down came the head once more. Again I grasped Ernest’s hands – he not so cheery, now, in fact rather pale – and we bounced upwards. We made it four or five feet off the floor before slamming violently down again. After a moment we could feel the whole frame shuddering as though someone were jumping up and down on top of us, and then all at once a great rattling, rustling, bumpity-bumping on the canvas right above our heads, and it all stopped.

The audience were laughing hysterically, now, at something. I peered down at the small portion of the brightly lit stage that I could see at my feet and was astonished to see the Rotter sitting there, in decidedly unprehistorical costume, holding his head and moaning. Evidently he’d been bouncing onto the top end of the creature, trying to provide enough counterweight to lift us clear, and had slip-slided all the way down the neck, ending up in a heap in full view of everyone.

Suddenly there was an ominous creaking from above, followed by a snapping, and then the whole mass of wood, and painted canvas, and rope, and pulleys crashed to the ground and splintered around us. The audience hooted with glee. Mr Kenyon crawled out of the wreckage over towards the orchestra pit and then vomited copiously over the kettle drums.

“Curtain,” the Rotter moaned in a tiny voice, clutching the area of his kidneys. “Curtain, damn it all!”

The audience leaving the New Theatre that night were thoroughly satisfied. The script had been funny, the songs agreeable, and then everything had fallen spectacularly to pieces at the death. What could be better? The next best thing, always, to an absolute smash hit is a notable catastrophe.

The Rotter and his engineering cohorts set about rebuilding and repairing their pride and joy almost at once, and I was dispatched up to the theatre bar to fetch drinks for everyone.

I had just finished loading a dozen Scotch-and-waters onto a tray when I heard a sarcastic little cough from behind me.

“That’s a powerful thirst thee’ve got there, young feller,” said a voice with a thick sort of accent I couldn’t quite place. I turned to grin at the speaker, who was a dapper little chap in a sharp suit and very shiny shoes.

“Yes, sir, and I’ll be back for another dozen in a minute. Excuse me…”

When I returned a few minutes later the bar was empty except for this gentleman, who was perched on a stool and, it seemed, was waiting for me. I slipped behind the bar and began pouring out more drinks.

“You were in t’ show just, weren’t you?” the man said, narrowing his eyes at me appraisingly.

“Yes, sir, I was.”

“You were t’ lad in yon creature’s mouth, were you not?”

“Yes, sir, that’s right.”

“Now then, that big red-faced feller tumbling down the neck and ending up scratching his head in the middle of the stage. I’m right, aren’t I? That weren’t meant to’appen?”

“Er, no.”

“Pity. That were t’ best bit.”

I’d filled my tray again by this time, so I smiled an end to the conversation and excused myself, but my companion hadn’t finished.

“You know, I came all the way up from London to see that beast. Thought it might be something I could use.”

I realised then that this chap must be one of the Rotter’s theatre contacts, one of the men he was hoping to impress.

“It’s very clever, really, how it works, and it was fine in rehearsals. I’m sure Mr Rottenburg could explain better than I what happened. I’ll run down and fetch him…”

The man held up his hand and said firmly: “No. Don’t fuss yourself. It’s not for me. No, laddo, it’s you I wanted to speak to. Now I’m watching you running up and down stairs carting d

rinks and I’m thinking you’re not one of these gentleman student types. I’m right again, aren’t I?”

“You are, sir,” I said sheepishly.

“So what are you? Servant of some sort?”

“I work for one of the colleges, yes, sir, general dogsbody work, portering and so on.”

“I see. Well, now listen to me. I saw how you handled yourself on the stage tonight when that whatsit fouled up, and I’m telling you straight that I liked what I saw. Now I’m not saying I’m never wrong, but I will say it hasn’t happened above once or twice since I’ve been in this business.”

I started to grin at this, but he didn’t, so I quickly reined my grin in.

“If you ever decide that you want more than general dogsbody work, portering and so on, you come and see me. You got me?”

He handed me his card, and shook me by the hand. I didn’t know what to say, quite, so I said: “Thank you, Mister…?”

“Westcott. Frederick Westcott.”

Then he popped his hat on his head and looked me up and down in a solemn fashion.

“When you know me better you’ll know I don’t say this lightly,” he said. “But you’ve got it, young feller me lad.”

“What?” I said.

“It.”

And he turned on his heel and left. I looked at the card he had given me and the name Westcott wasn’t anywhere to be seen. The inscription read:

“FRED KARNO

MASTER OF MIRTH AND MAYHEM

The Fun Factory, 26–28 Vaughan Road, Camberwell, London SE5”

I didn’t know it then, but my life had just changed for ever.

5

The Fun Factory

The Fun Factory